Landscape as dialogue

The relational experience of the landscape to understand a space and transform oneself

I wrote a book…

… about the process of evaluating the landscape as a collaborator with place. It rejects traditional site analysis, with its divisions and properties, and embraces a dialogic approach. Designers join an ongoing conversation with the landscape to understand how that place has been produced over time. And how it might change for the better.

The book offers methods of understanding the landscape holistically. It is written for architects, landscape architects, planners and students. It is now published!

Available in the following places:

For a PDF of the draft introduction, link here…

Here’s the cover… with a red border that eventually went away.

From a visit to the Almendres Cromlech near Evora, Portugal, c. 6th century B.C.

Table of Contents

-

In traditional site analysis, designers divide landscape elements into categories, i.e. soils, circulation and land use. Yet the landscape is not an assembly of disparate parts but an active and changing whole. This book examines the process of landscape dialogue, a give and take with the integrated cultural and environmental world. What if designers of the landscape, instead of extracting information to master it, were to engage the landscape in dialogue to transform it and themselves?

-

Landscapes change; they flow. It is the dynamic quality of design and the need to accommodate decades of change that informs the design practices. Using landscape ecology, this chapter examines landscape dialogue from the perspective of the landscape… what is it trying to tell us? And why do people have such a difficult time anticipating landscape dynamics (i.e. building in a floodplain)? Designers must anticipate future landscapes from past and present movements, while communicating to others the importance of change. In this chapter, we examine the Japanese tsunamic of 2011, the shifting nature of the landscape and its connections to local histories.

-

Conventionally, landscape architects read the landscape for information. We divide things up based on discipline and put them back together, reifying the disciplinary hierarchy of universities, extension programs and government. The cycle of analysis and synthesis helps focus and learn, but also ignore and divide. What if we considered the social and environmental landscape as a whole? While that is the goal, landscape architects need to understand the language of disciplines to contribute to the remaking of our cities, our towns and our rural landscapes. This chapter examines the breaking down of landscape components as it relates to eventual design synthesis, while providing alternatives methods of measuring diversity and complexity in the landscape.

-

How does one make sense of the landscape? Can the landscape be read? Our relationship to the landscape begins with perception, our sense of the world. Alva Noe (2004) says perception is action; we perceive by doing. The landscape is not a picture, but an experience. The key aspect of perception in the landscape is movement through the cultural conditioning that shapes what we see and hear. At times, our cultural perceptions as experienced can dramatically change our experience of reality. I examine three aspects of perception of landscape: 1) site and the bounding or partitioning of space/property, 2) speed and the viewing of place (e.g. from a car), and 3) stasis or the inability to see the landscape as a changing and dynamic process, (e.g. building in a floodplain).

-

To transcend the categorization of landscape information, designers immerse themselves in the landscape as part and parcel of that place. An immersive approach retains an experiential view of the whole landscape. Our experiences, based on education, professional work but most of all, a continual attention to place, guide us in our collection of “data” to evaluate a space. Immersion holds in tension multiple contradictions found in the landscape without separating them from the space. It is a challenging practice. I use case studies from the National Park Service and a Chinese garden to illustrate practical approaches to immersing oneself in a way that reinforces initial impressions in a way to guiding future design.

-

This chapter wrestles with landscape as relational; the space between us. We relate to others as located beings with our own unique relationship to the landscape. I examine the process of establishing wildlife crossings along U.S. 93 in the Flathead Indian Reservation of Montana to elucidate ideas of power and decision-making. If landscape is produced by relations, how do power differences shape a place? Landscape extends to broader, global forces, positions and geometries. Designers should be able to map or diagram these relations, question their imbalance and propose more equitable design solutions.

-

To critique the landscape, designers should understand relations and power dynamics before dismantling hierarchical ideas of structure and “that’s the way it’s always been done.” What does it mean to be critical? The landscape speaks of a city’s priorities, a town’s hierarchies, a region’s relationships with other places. Landscape dialogue requires critical listening to existing inequities. It questions taken-for-granted beliefs such as a certain type of economic growth, such as “public space equals roads” or “Civil War heroes should be honored” – prevalent in the landscape. This takes a sensitivity to overlapping local histories. Landscape critique can be political, disrupting notions of what is “sensible” in the partitioning of the cities and towns of America (see Rancière, 2015). Critique inspires the designer to move from understanding conflict to advocacy. The use of countermapping, sketching and archival research exposes structures in the landscape and may suggest design alternatives.

-

Public landscapes are places of interaction and therefore conflict. Designers need to understand past conflicts in order to provide space for future positive challenges and change. Conflict, between inhabitants, between the national or regional visitor and the local resident, can mean difference in opinion that gets resolved through open-minded design or it can mean active violence (shootings) or passive violence (segregation, gentrification). I turn to the work of Eyal Weizman and forensic architecture to examine how design offers a method of analysis of violence, real and implied. Methods are based on space and events, rather than landscape elements. Conflict in and about the landscape is not always negative; it can include protest and advocacy for change. Designers can inhabit dissent through protest, through tracing paths of conflict which are methods of landscape dialogue.

-

Landscape dialogue leads to an opening of the designer to personal and professional change. A dialogue with the landscape is an exchange, a negotiation of interdependent positions. While site analysis draws information from the landscape to shape it or as some consider, to master it, landscape dialogue listens to the landscape to undergo personal growth and formation. The experience of landscape, positive or negative, is formational. The designer immersed in place changes through the myriad of influences and inputs that stem from being open to place. The chapter asks: what would it look like to rely on landscape as a formative part of one’s life? The power of landscape – not a power bequeathed from planners or politicians but power inherent in the movement of wind, air, people and materials as they continuously shape a place – transforms us into more sensitive and stronger designers, more passionate and thoughtful people.

-

If landscape assessment is a form of dialogue then the role of designer appears straightforward; we are to listen to understand, then speak through drawing and design. Yet, landscape dialogue implies more than that: a responsibility as designers to respond to the landscape and its uneven qualities so as to transform space into a more just and healthy place. I end our discussion with a brief framework of landscape as dialogue to be used as a basis for design.

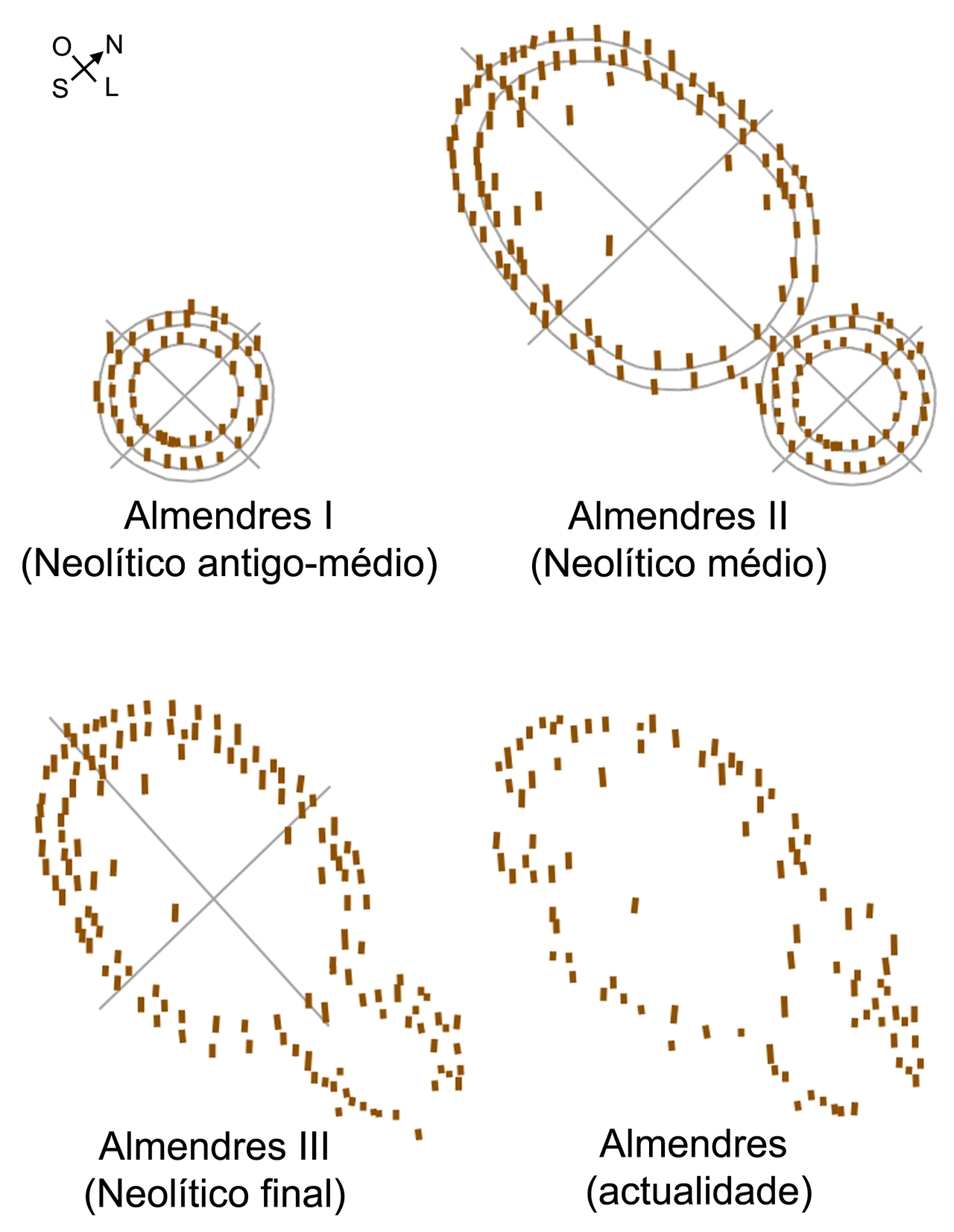

Almendres Cromlech over time, Fulviusbsas, CC 3.0

Landscapes change over time…

… and our evaluation of the landscape should embrace change and the temporal.

When we analyze the landscape, what is it we are doing? We perceive our surroundings through multiple senses: seeing, hearing and touching the environment. We form impressions of a place filtered through past experiences of other places both similar and different. We focus on certain landscape elements based on an aesthetic response, both positive and negative. We observe how others interact with a space. We take impressions of the landscape and our scientific and not-so-scientific understanding of a place and draw them, write them down as notes, take them back to an office or home, and let them stew.

When we analyze the landscape, what is it we are doing? We perceive our surroundings through multiple senses: seeing, hearing and touching the environment. We form impressions of a place filtered through past experiences of other places both similar and different. We focus on certain landscape elements based on an aesthetic response, both positive and negative. We observe how others interact with a space. We take impressions of the landscape and our scientific and not-so-scientific understanding of a place and draw them, write them down as notes, take them back to an office or home, and let them stew.